Theatre games and their many flavors

I was chatting with a fellow teaching artist recently about creating more efficient lesson plans. We both agreed we’d like to “cut the fat” and get to the meat of each lesson, but struggled with our limited time with students. My colleague said something that I had a strong reaction to — they said, “maybe I should just cut out some of the theatre games from my lesson plans so we have more time for the learning objectives.” I audibly gasped. Not the theatre games! Those are the best part! We continued talking about blending learning objectives into theatre games (i.e. sneaky learning, haha!) but my strong reaction stuck with me. Why did I feel so strongly about theatre games?

As a former quiet kid, theatre games were an open door to expression that I otherwise felt distant from. My first theatre class was in middle school, a universal pit of self-esteem for most students. I was incredibly timid to open up to strangers about my inner life — as a nervous child, staying quiet and to myself was the safest option. In theatre, I could carry this nervousness into my acting and make safe, timid choices for my characters. I had trouble projecting my voice, enunciating my words, and taking up space on stage. But this wasn’t true when I played theatre games. Why? Because I wasn’t in the driver’s seat of my choices! For example, if my teacher told me to “walk across the stage” I’d more than likely shyly trot across with my head down. But, if my teacher had us playing a game where we had to “hop across the stage like feral little bunnies,” I’d do it. I’d feel embarrassed and weird, but I’d do it. And I had fun. And then the next time it wasn’t as embarrassing. And I laughed with my peers. And I made friends! And I came out of my shell! Ah, the miracles of theatre games!

Now as a theatre educator myself, I’ve learned not all theatre games are created equally. And just throwing a theatre game into a lesson willy-nilly may cause chaos and confusion. Theatre games should be planned mindfully and with intention. Ideally, they should connect to the day’s learning objective and give students time to practice a skill they can put in their figurative toolboxes. Below are a few genres of theatre games that I find useful to consider when planning a lesson. So… are we playing a game today?

Competition

After getting to know my students, I learn who does OK with losing and who doesn’t. Typically it’s the best buddy duos who have the most beef with each other. Sometimes an entire class is incredibly competitive with one another, and sometimes it’s just 2-3 students who go head-to-head during games. To keep all students tuned in during a theatre game at the start of a lesson, I tend to choose games that don’t have clear losers and winners. A game that encourages collaboration and creativity is a great way to open class. Any game that we can play in a circle is a great option for competitive groups.

For example, a fun lower energy game is Dictionary. In a circle, Student 1 makes up a word. Student 2 makes up that word’s definition, Student 3 uses the word in a sentence, and Student 4 makes up a new word, Student 5 gives Student 4’s word a definition, and so on. Students get to be silly and creative without the fear of losing. Games like Zip Zap Zop and Night at the Museum are a hoot, but they have immediate losers who become disengaged once they’re sitting on the sidelines. I save these types of games for the very end of class to burn off any extra energy.

Focus

Y’all remember Mother May I? It’s a wonderful focus game that’s like salve for classes with especially chatty students. It requires complete focus for the entirety of the game. It’s also a great way to stretch and warm-up by diversifying how students are allowed to move across the stage. For example, the “Mother” student will tell their peer to “take 2 giraffe steps” or “take 3 slithery snake scoots.” The student must then ask Mother for permission — “Mother, may I?” — before they move. Students quickly learn they need to be quiet and focused in order to reach Mother first. They can even be creative with the call and response. One of my classes renamed Mother to “Non-binary Guardian” which they all giggled endlessly at. So be it! There is a winner of the game (whoever reaches Mother/Non-binary Guardian first), but until then everyone’s vying for the big win.

Improv

Improv! Improv! Improv! An essential element of any theatre instruction. Despite being a wonderful jungle gym for students to play in, improv does need firm boundaries. Otherwise, it’s just playtime and the students will go wild. I like using improv games to warm-up my students’ creative brains and get them thinking how characters can relate to each other.

One improv game I really like doing is called Actors & Dubbers. One group of students, the Actors, speak in gibberish to each other. Another group, the Dubbers, must translate the gibberish into a scene with their fellow Dubbers. Clear directions are vital here, otherwise it’s just overlapping gibberish and silly (borderline unintelligible) improv. First, we review basic improv principles like adding new information and saying “yes, and” to their fellow actors. Then, we talk about sharing talk time and avoiding interrupting each other. I tell them to think of me as the audience to their show. I can’t understand the show if everyone’s speaking at once! Encouraging them to work together, speak slowly, and really try to translate (and not just making up a random goofy sentence) helps with this specific game. Improv is fun and freeing but it requires rules, direction, and clear boundaries to be at its best.

Leadership

I adore theatre games that call for a leader or captain who calls the shots. Typically, I will ask one of my more quiet or reserved students to be the leader of these types of game (and give them the option to say no, which is OK!). This gives the leader student a wonderful opportunity to take authority and have their voice not only heard, but respected. Even outside of theatre games, I like to welcome students into leadership roles during class to flex their agency.

One specific theatre game that works well for student learnership is Who Started the Motion? The students stand in a circle, looking at each other in silence. One student, the Guesser, closes their eyes as the rest of the students silently decide who will start a motion. This student, the Mover, will start a movement that the rest of the circle must repeat. Clapping their hands in rhythm, tapping their head, stomping a foot, etc. The Guesser must turn around in the circle and guess who’s the Mover — when the Guesser’s back is to the Mover, the Mover gets to change the motion which the rest of the circle must follow. This game is almost completely nonverbal which works well in classrooms with different abilities or languages.

Collaboration

When a lesson plan requires small group time where decisions need to be created and agreed upon, I start lessons off with heavy collaboration focused games. Especially when I work with students after school, sometimes the children are tired of each other. I get it! I like to play theatre games that demonstrate teamwork as a crucial element to fun.

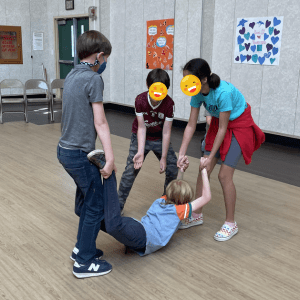

For example, the simple game of Count to Ten. This is best for grades 5th and over. The group sits in a circle, facing each other, and are told they must count to ten. Without speaking or communicating in any way, a student must start by saying “one,” followed by another student saying “two,” and so on. If students speak at the same time to say a number, the group must start back at one. The students will eventually fall into a nonverbal ~vibe~ with each other, sit in silence, and speak when they feel called to. Sometimes it takes a couple of minutes and sometimes students work on it for an entire 10-week program. Loads of frustrating fun! An alternative game is Human Knot where students grab each others hands at random and have to (safely) twirl, unfurl, and unwind to create a giant circle or several smaller circles. Students are allowed to speak during this game and there are a bunch of leadership opportunities here. Again, frustrating fun!

When I’m working with K-4 students, I like to play Yes Let’s. The rules are simple: The teacher picks a group activity (going to the zoo, park, etc.) and each student must one-by-one choose an action, pantomime it, and then the group must agree and follow. For example, if the activity is “we’re planning a birthday party.,” a student could say “Let’s buy a cake.” That student would pantomime buying a cake. The entire class must then say “Yes, let’s do that!” and follow pantomiming the action. The next student could say “let’s eat all the frosting,” pantomime eating the frosting, the group says “Yes, let’s do that!” and pantomimes the action. This continues on until everyone has suggested something. By the end of the game, the students will have repeated the phrase “Yes, let’s do that” several times, thus planting the seed that accepting others’ ideas can be easy and fun. Woohoo, sneaky learning!

So, in summary…

It’s freeing to not make a fool of yourself, to make wild choices under the safe umbrella of a theatre game. With a teacher’s encouragement and direction, theatre games can allow students to share their inner selves with others. Theatre games, and great educators, introduced me to self-confidence and feeling like I belonged with my peers. As a theatre teaching artist, theatre games will always remain in my lesson plans. They’re freeing, encouraging, and vessels for sneaky learning. Also… they’re FUN! And that’s important!